git-workshop

Git Expert - Distributed Workflows

| Is this section core or elective? | Expected time to completion |

|---|---|

| elective | before last meeting |

Goal

This section deals with Git workflows, which are recipes for working together with Git in a consistent manner. We will focus on the most widely used workflows. After this chapter you should know how to contribute code in most projects.

Introduction

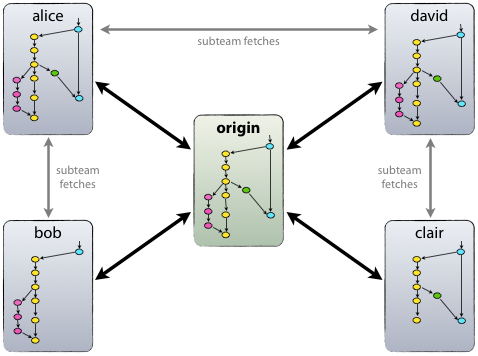

Git is a distributed version control system (DVCS). Hence Git allows that each developer or team has their own repository - not just locally on their computer but also stored on a server somewhere. It is not necessary that a central Git repository exists, i.e., a repository with which every developer directly interacts. However, on most projects there typically is one, and on most d-fine projects you will therefore use a centralized workflow.

Some facts to keep in mind about distributed workflows and repositories:

- Different repositories can all be in a different state.

- Arbitrarily complex workflows are possible, with the workflow usually chosen based on the size and organizational structure of a project.

- A private repository can only be cloned and viewed by its owner and any collaborator the owner chooses. Local repositories are nearly always private.

- A public repository is visible to everyone who has access to the “location” of the repository. Meaning, if the repository is created on GitHub everyone on the internet can access the repository. Especially, everyone is able to create a fork as starting point of its own new project. Public repositories are usually stored on a server.

Now we will introduce the most common workflows in ascending order of complexity.

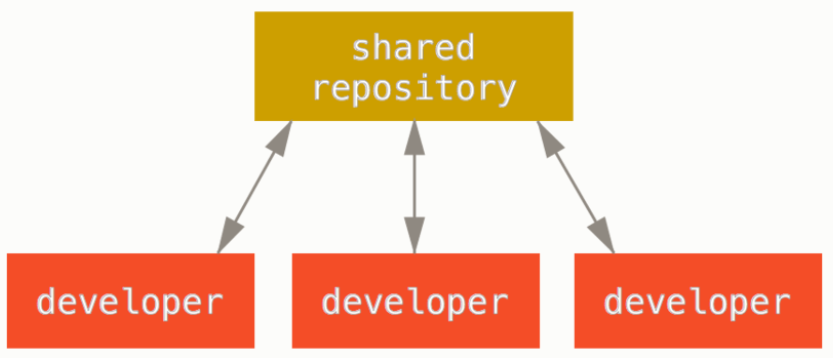

Centralized Workflow

In a centralized workflow a single central repository exists. All developers work on their clone of this repository locally and commit and push their changes directly into the central repository.

source:

https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Distributed-Git-Distributed-Workflows

source:

https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Distributed-Git-Distributed-Workflows

Without further means, this workflow does not enforce a four-eyes principle or a code review. However, Git servers such as GitLab or Bitbucket are often configured so developers cannot push their changes to any branch, but only to feature branches, effectively protecting the main development and release branches.

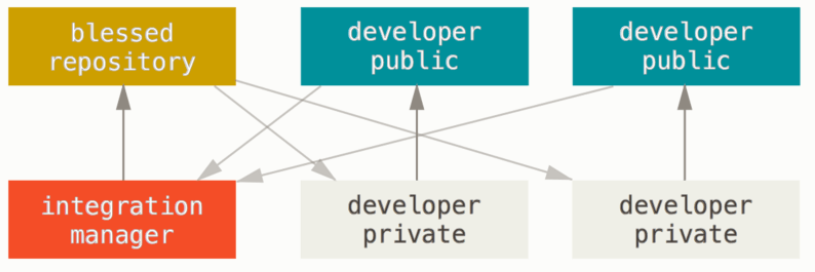

Integration-Manager Workflow

Every developer has two repositories: A public one and a private one. Additionally, there is a special repository, often designated ‘blessed’, with the official project code. Furthermore, there is one special developer designated as the ‘integration manager’. The workflow is as follows:

- Developers clone the state of the blessed repository.

- Then they work in their private repository and eventually push their changes to their public repository.

- A developer sends the integration manager an email asking her to pull the changes.

- The integration manager pulls from the developer’s public repository and reviews and merges the changes locally.

- The integration manager pushes the merged result to the blessed repository.

source:

https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Distributed-Git-Distributed-Workflows

source:

https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Distributed-Git-Distributed-Workflows

The integration manager workflow enforces a four-eyes principle. Another advantage for larger development teams over the centralized workflow is that the main repository does not become cluttered with feature branches.

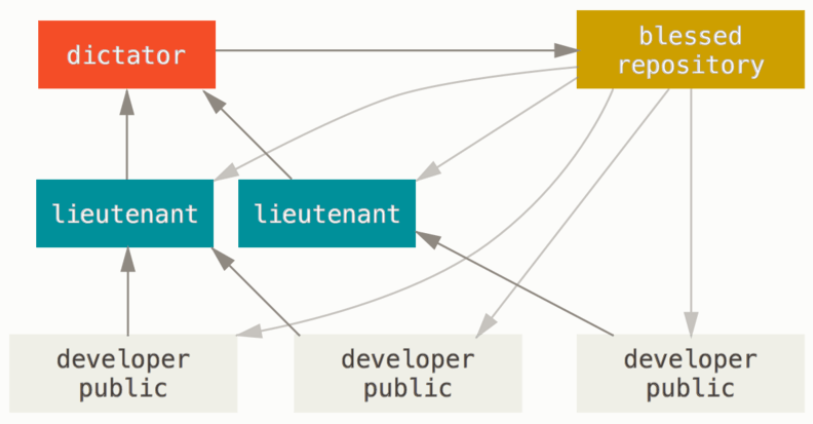

Dictator and Lieutenants Workflow

In this workflow, developers again work within their own repository. Afterwards, they inform the “lieutenant” that their changes are ready for a review. The lieutenant locally merges the changes from the remote repository into the current state of the blessed repository. After a review and functional tests, the lieutenant pushes the local changes into her public repository and informs the “dictator”. The dictator locally merges the changes of the lieutenant’s remote branch in the current state of the blessed repository, checks everything again and finally pushes that state into the blessed repository.

source:

https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Distributed-Git-Distributed-Workflows

source:

https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Distributed-Git-Distributed-Workflows

This workflow scales to any number of developers and safeguards the main repository very well due to at least two code reviews. It is used for the development of the Linux kernel.

Commands in Git

-

git remote

Manages remote repositories. -

git fetch (<repo>) (<remote branch>)

Fetches all changes from remote repo (and named branch). -

git pull (<repo>) (<remote branch>)

Fetches all changes from remote repo (and named branch) and merges them into the current branch. -

git push (<repo>) (<local branch>:<remote branch>)

Pushes the changes from local branch onto remote branch. -

git push -f (<repo>) (<local branch>:<remote branch>)

The -f is the short form of “–force” and it overwrites the remote repository branch by your local one. This means that any upstream changes (changes in the corresponding remote branch) that may have been done since your last pull are deleted. It should only be used after a commit –amend. For a more detailed explanation, see here.

Changing history

The following commands should only be executed with caution.

-

git commit --amend

Amends the last commit instead of creating a new commit. You should only use it, when you have to fix the last commit and none of your teammates have pulled this commit before you can push the fix with “–force” option. More details on this can also be found here. -

git rebase (-i)

Allows modifying, skipping, or squashing all commit since the named one. One basic command is ‘git rebase <upstream> <currentBranch>’. Here, all applied commits from your currentBranch are locally applied again on the current head of the upstream branch. You are locally still on the <currentBranch> but the history has changed. More details on this can also be found here.

Exercise

Remember how to submit solutions.

Imagine we have a developer Alice, who works on a software product, and also has created her own local copy of a shared remote repository.

Setup

- Setup a local repository in a folder named

remoteas a bare repository (use the--bareoption withgit init). - Clone that repository into a folder named

repoAlice. - Create some changes in repoAlice and push them to the remote repository.

Alice starts developing two new features at the same time. In order to do so, she creates a feature branch for each of the two new features and pushes her changes accordingly.

Push, Pull and Change History

Exercise 1 (in repoAlice)

- Create a featureOne branch from your current master branch.

- Create a second featureTwo branch from your current featureOne branch.

- Checkout the featureOne branch. Add some changes, commit, and push them.

- Checkout the featureTwo branch. Add some other changes, commit, and push them.

- Compare the history of your featureOne and featureTwo branches.

After Alice pushed changes into both feature branches she notices that feature two depends on feature one and should have rather been build on top of the changes of feature one instead of both features starting on the same code base.

- Rebase your entire featureTwo branch onto the featureOne branch.

- Compare the history of the two branches. What has happened?

Imagine now a second developer Bob joins Alice working on the same software product. Since the changes which have to be made for feature one are very complex they both work on feature one simultaneously. Since Alice has already pushed some first changes into the featureOne branch in the remote repository, Bob has to pull her changes into his local copy first.

Exercise 2 (in repoAlice and repoBob)

- Create a second clone of the remote repository in a folder called

repoBob - In repoAlice: Push all changes of the featureOne branch to remote.

- In repoBob: Pull all changes of featureOne, such that both Alice’s and Bob’s local repositories are now identical regarding the branch featureOne.

- If you have not done so already, switch to the branch featureOne on both repoAlice and repoBob.

Alice notices that she accidentally pushed incorrect changes to the remote repository, therefore she amends her last commit in the remote repository. Afterwards, Bob can pull the amended commit into his local repository.

- In repoAlice: Amend your last commit by making some changes and commit –amend them.

- In repoAlice: Push your changes to the remote repository. (Hint: you have to use –force)

- In repoBob: Pull the changes in the featureOne branch.

- Compare the histories of featureOne in repoAlice and repoBob. What effect did the force-push have? Was commit –amend a good idea?

- What command do you need to execute to get content and history of the featureOne branch in repoBob in line with the featureOne branch in repoAlice and remote?

Further reading

- Git-SCM - Distributed-Git-Distributed-Workflows

- Git-SCM - Git Rebase

- Bitbucket Git - Comparing Workflows

- Bitbucket Git - Syncing

- Atlassian Git Tutorial - Git Push